Why I refuse to fill lips anymore…

Fuelling desires

It was 2005, and I was about to open my clinic.

When it came to naming the business, I sat down with my business partner and our advisor. We wanted a name that carried weight – something that made us sound bigger than we were then, maybe something to aspire to become.

We settled with ‘Victorian Cosmetic Institute’. “Victorian” located us. “Cosmetic” described what we did. And “Institute” made us sound like a place of research, study, or serious medicine – even though in reality, we weren’t conducting studies.

Instead, we were ‘fulfilling’ the desires of our patients, including many requests for lip filler over the years.

As aesthetic medicine has evolved, so have the preferences of many of my patients. I’ve noticed a decline in requests for excessively large lips, but I still frequently encounter patients, especially those I have previously treated with lip fillers, who ask, “Can I have just a little bit of lip filler?”

I now refuse, even to the ‘just a little’ requests. Let me explain why.

The science behind our desire to have fuller lips

‘My lips are my only publicly displayed sexual organ, and that’s why I want them enhanced, doc…’, is something I have never heard any patient tell me.

Instead, the reasons patients provide are more covert:

‘I want my lips to look fuller, like how they used to look’

‘I just want to feel more confident about my lips.’

But there is a subconscious biological drive to have lip enhancement.

Fuller lips are evolutionarily associated with youth, fertility, and high oestrogen levels – cues our brains are wired to find attractive.

This may be further reinforced by the fact that plumper lips are rewarded on social media with likes and attention, subtly training our brains to seek – and maintain – that look.

“…I used to get them done so that I would feel more like I fit in, so that I’d look more like pretty and you know just fit in with everyone. At that time I think it was because I felt more insecure. Once I had them [fillers], I kind of felt like, now I’m getting a good amount of attention (which I was definitely getting more of) and I suppose that’s what pushed me to get it again and again. Because I felt like, everyone is doing it, it’s all over social media, and I just wanted to be part of that…” – Lottiexxxx

Excerpt from: Redefining Beauty: A Qualitative Study Exploring Adult Women’s Motivations for Lip Filler Resulting in Anatomical Distortion

Add to this the widespread belief that lip filler is low-risk and easily reversible, and you create the perfect conditions for the casual use of lip filler.

A significant proportion of individuals seeking cosmetic treatments meet the criteria for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), a mental health condition often associated with repeated aesthetic procedures and chronic dissatisfaction with appearance.”(ScienceDirect)

Getting “a bit of lip filler” may not be as harmless as it seems, and it’s not just due to self-image issues. The process can often lead to a psychological cycle: initial excitement, gradual normalisation of the new size, followed by dissatisfaction, and ultimately a repeat treatment, which reignites the initial excitement.

“…It was really bizarre, the whole psychology of it… Looking back at them now, they were really big, but at the time, I was adamant I needed more… really strange…” – Alice

Excerpt from: Redefining Beauty: A Qualitative Study Exploring Adult Women’s Motivations for Lip Filler Resulting in Anatomical Distortion

At first glance, the desire for fuller lips may seem superficial. In reality, the “why” behind lip filler is rarely simple – it’s a complex blend of biology, beauty culture, and emotional need, backed by scientific evidence.

And while scientific evidence may explain why larger lips might be beautiful and desirable, it doesn’t always justify fulfilling the wishes of everyone who asks.

When Practitioners Become the Advertisement

Attend any major cosmetic conference, and you’ll notice a consistent – and often unspoken – phenomenon: many of the practitioners leading the talks or demonstrations have visibly overfilled lips themselves, in some cases dramatically so.

They’re not just teaching techniques; they’re embodying a particular aesthetic – one that has drifted far from natural human anatomy. And whether intentionally or not, they become the living advertisement for that look.

This becomes problematic when it’s no longer just a matter of personal preference. What we’re seeing is a perceptual shift – not just in patients but also in practitioners themselves.

Dr. Steven Harris explored this issue in his 2022 study published in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. The findings were eye-opening: 16.6% of aesthetic practitioners screened positive for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), compared to just 2.2% of aesthetic patients.

📚 Read the study: “The Devil’s in the Details: BDD in Aesthetic Practitioners” (Harris & Waller, 2022)

When an injector’s own aesthetic compass is altered – whether by BDD, overexposure to extreme results, or years of self-treatment – that distortion doesn’t stay private. It often gets projected onto their patients.

In other words, a practitioner who sees their own overfilled lips as normal, it is more likely to guide patients toward that same exaggerated standard. Not necessarily out of malice, but because their perception of beauty has been recalibrated – and they may no longer realise they’ve crossed a line.

This creates a dangerous feedback loop: practitioners with distorted aesthetics influence patients, who then request more extreme results, which in turn reinforces the practitioner’s own bias.

The result? An industry where both sides – practitioner and patient – are drifting further from natural proportions, convinced all the while that they’re simply following beauty.

But Why Can’t You Just Have a Little Bit?

It’s a question I hear often – “But what if I just have a little bit of lip filler?” In theory, it sounds reasonable. Conservative. Measured. But in reality, it rarely stops there.

One of the reasons is the initial post-treatment effect. After injection, the lips typically appear more swollen, defined, and voluminous than they will once the swelling subsides. This temporary fullness – what some call the “day two look” – is often what patients fall in love with. It’s dramatic, plush, and photogenic. But it doesn’t last.

When the swelling settles and the true volume is revealed, many patients feel underwhelmed. They return, not because the treatment failed, but because they’ve become attached to that transient, exaggerated version of themselves. The effect is psychological: the brain recalibrates, and suddenly, even naturally proportioned lips feel small.

This isn’t a chemical addiction, but a visual and emotional one. That rush of seeing plumper lips, coupled with the dopamine hit from compliments or selfies, becomes something patients start to chase. A little more. Then a touch-up. And before long, subtlety gives way to excess.

That’s why the idea of “just a little” so often becomes a little more, again and again.

Most lip fillers are made from hyaluronic acid and are marketed as lasting only 6 to 12 months. If that were truly the case – if these fillers were genuinely temporary – the risk would seem minimal. But growing evidence, including MRI studies, shows that filler can persist in the tissues for years, often migrating beyond the lips and accumulating over time. So what begins as a seemingly harmless enhancement can quietly become a long-term alteration of facial structure.

The Myth of “Short-Lived” Fillers

One of the most persistent myths in aesthetic medicine is that hyaluronic acid fillers only last 6 to 12 months. Patients are often told they’ll need to “top up” their lips every six months – a cycle that seems harmless enough. But this timeline is based more on marketing than on science. In reality, filler can last much longer – and not always in a good way.

Dr. Mobin Master, a Melbourne-based radiologist, conducted a series of MRI studies that turned this assumption on its head. His 2021 study revealed that hyaluronic acid filler can persist in facial tissues for years, often in unexpected locations, well beyond the injection site.

These findings showed that filler frequently migrates and may remain undetected for years unless specifically imaged.

Specifically, lip filler can migrate beyond the vermillion – the red portion of the lip – creating the impression that it has “worn off.” In reality, the filler often remains in the tissue for many years, just displaced from its original position, leading patients to believe they need a top-up when the product is still present.

Repeated top-ups can lead to an accumulation of filler in the area, resulting in an unnatural, blurred fullness of the lips and surrounding mouth. Ironically, this rarely recreates the sharply defined look of freshly placed filler that the patient is trying to recapture. Yet, in pursuit of that original effect, the patient continues to have more filler injected – unknowingly compounding the problem.

However, the reassurance that lip fillers are “reversible” often creates a false sense of security – leading patients to feel more comfortable going ahead with treatment, or even returning for more. The logic becomes: If I don’t like it, I can always dissolve it. But this mindset overlooks the reality that while filler can be removed from the tissue, the psychological impact – the altered self-perception and growing attachment to a fuller appearance – is not so easily undone.

The Illusion of Reversibility

Lip filler is often sold as temporary and reversible. And technically, that’s true – hyaluronic acid fillers can be broken down using hyaluronidase, an enzyme that dissolves the product. But in practice, the story is far more complicated.

Over time, patients don’t just adapt to the physical presence of filler – they become psychologically attached to the enhanced version of themselves. Even when the lips have become misshapen or puffy, the larger size feels familiar. Natural begins to feel inadequate.

In my own clinical practice, I’ve seen this repeatedly: patients who ask to have their lip filler dissolved, only to request it be put straight back in. What they’re really struggling with is not volume loss – it’s visual recalibration. Their internal standard for what looks “normal” has shifted. This is consistent with research on perceptual adaptation. A 2021 study by Walker et al., published in Body Image, demonstrated that repeated exposure to exaggerated or filtered features can cause individuals to recalibrate their visual norms – making natural features seem underwhelming by comparison.

This process often feeds a cycle of re-injection, which resembles behavioural addiction – not to a substance, but to a feeling or identity. As Dr. Steven Harris has discussed extensively in his work on “filler addiction,” some patients keep returning for treatment despite increasingly unnatural results, and sometimes even after reversal. The desire isn’t rational – it’s emotional.

This issue is compounded by the high rate of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) in cosmetic settings, where the combination of addiction and dissatisfaction can compound the problem.

When such patients undergo reversal, the return to baseline doesn’t bring relief – it often triggers distress. And rather than accepting their natural anatomy, they seek to restore the very changes they wanted to undo.

So while lip filler may be reversible in theory, it is often irreversible in practice. Because what lingers isn’t just the product – it’s the patient’s relationship with the way they looked at their fullest. And that’s much harder to dissolve.

The Physical Limits of Lip Filler

There’s a common misconception that lip filler can dramatically transform lips – turning thin or flat lips into plush, pillowy ones with just a syringe or two. In reality, the physical limitations of filler are often overlooked by both patients and injectors.

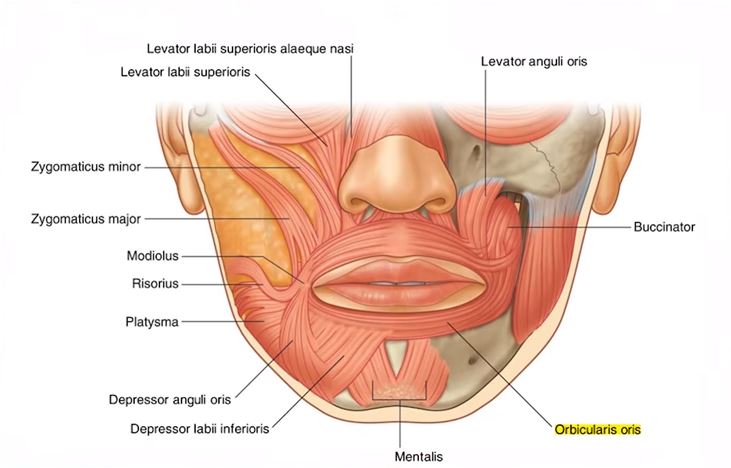

Lips are not an empty vessel you can keep filling. They are dynamic, mobile structures with finite space, made up of tightly bound connective tissue, muscle, mucosa, and skin. Once that capacity is exceeded, the filler doesn’t just disappear – it migrates. This is especially true with repeated treatments or overfilling, where the product is pushed beyond the vermillion border into the surrounding tissue, blurring the lip line and creating that telltale puffy or “sausage” look.

Ironically, smaller lips – the very ones patients most want to enlarge – are the hardest to treat. With less space and less tissue compliance, even conservative amounts of filler are more likely to spread rather than build structure. This can lead to distortion rather than enhancement, particularly over time.

And while hyaluronic acid fillers are marketed as lasting 6 to 12 months, this doesn’t reflect what happens to the filler – only what happens to the visible effect. Often, the product doesn’t simply degrade and disappear; instead, it migrates and persists, lingering in surrounding tissue while the lip itself loses definition. This leaves patients feeling like their filler has “worn off,” when in fact it’s still present – just in the wrong place.

So the idea that you can keep enlarging the lips safely and predictably with each session is a myth. There is a structural ceiling, and pushing past it doesn’t create beauty – it creates bulk, distortion, and long-term complications.

And here’s the irony… the smaller the lips, the harder they are to fill. While they’re the ones most patients want to enhance, their limited space and tighter tissue architecture make them less accommodating to volume. Even small amounts of filler can create disproportionate pressure, leading to migration beyond the vermillion border.

In the End, We Can’t Have “Just a Little Bit”. Where It Leaves Me Now

Looking back, it’s clear that much of what I was doing early in my career was about fulfilling desire – not just the patient’s, but perhaps also my own: to grow, to succeed, to be relevant in an industry built on transformation.

Lip filler seemed harmless enough at the time. Reversible. Popular. Easy to administer. Patients were happy, and I believed I was giving them what they wanted. But over the years, I saw how those desires could warp – how filler didn’t just change faces, but changed the way people saw themselves. It became clear that we weren’t just adding volume; we were fuelling a cycle of dissatisfaction, distortion, and dependence.

Today, I no longer offer lip filler. Not because it never works – sometimes it does. But because the line between enhancement and harm has become too thin, too easy to cross. Because “just a little” almost never stays little. And because I’ve seen too many patients return chasing an effect that doesn’t exist anymore – or never really did.

What I’ve come to value more – and what I believe aesthetic medicine should return to – is supporting the integrity of the face: improving skin quality, restoring healthy structure, and knowing when to stop. There’s beauty in balance, in restraint, in letting go of trends that no longer serve us – which is why I refuse to fill lips anymore.

In the end, lips don’t need to be filled to be beautiful. They need to be respected for what they are – expressive, human, and already enough.